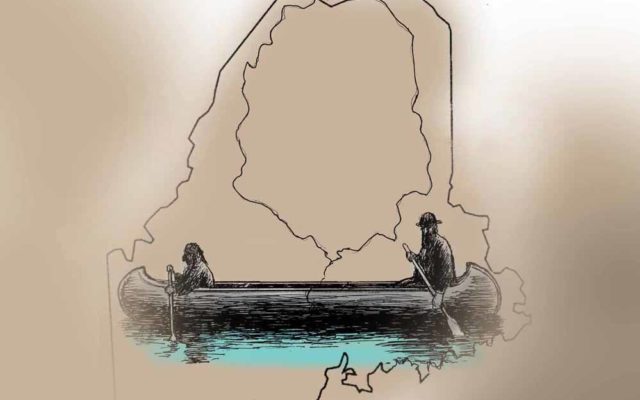

In 1820, one man journeyed into Maine’s great unknown. The other paddled through home.

Editor’s note: The writer of this article, Emily Burnham, is a descendant of Joseph Treat on her mother’s side.

The woods and waters of what is now Piscataquis and Aroostook counties were largely uncharted territory for the people of European descent in Maine in the years prior to statehood in 1820.

But for the Wabanaki people, who had lived along Maine’s rivers and streams for countless generations, the land was a family member. Thousands of years of ancestral knowledge made them intimately familiar with every bend in the river, every seasonal change in water level, the shape and size of every island, rock and mountain.

So when Maine became a state in March 1820, one of the first things decreed by Gov. William King was the need to more accurately map Maine’s vast interior wilderness — untouched in the eyes of the state, but home for the Wabanaki.

King asked Maj. Joseph Treat, a Bangor-based surveyor and son of a wealthy merchant family, to lead an expedition up the Penobscot and Allagash rivers and down the St. John River. Treat was part of a family of Treats who were among the region’s earliest white settlers, and had been living along the lower Penobscot River since the 1750s.

Knowing he would never be successful in the task at hand without help, Treat hired John Neptune, lieutenant governor of the Penobscot tribe, to be his guide. Their vessels were the perfect watercraft for river travel and something refined over generations by indigenous people across North America: two birch-bark canoes.

Treat and Neptune’s three-month journey in the fall of 1820 was like a microcosm of the Lewis and Clark expedition that occurred 15 years earlier: a fact-finding mission on behalf of a new government that would have been impossible without indigenous assistance. Its impact is still felt today in how it codified a relationship between the state and the tribes that continues to be a source of tension in both worlds.

Strange canoe fellows

Treat and Neptune set out from Bangor on Wednesday, Sept. 27, 1820, accompanied by Capt. Jacob Holyoke in two birch-bark canoes. Though the relatively late start meant they ran the risk of encountering cold weather and even snow, it also meant that river levels were low enough to allow an easier passage on the water.

By Sept. 30, the trio had gone 60 miles upriver to Mattawamkeag Point, where the town of the same name lies today, and where John Attean, governor of the Penobscot tribe, had his residence. Thirty-three years later, Attean’s son, Joseph Attean, would lead Henry David Thoreau on a similar canoe trip on the Penobscot.

They then made their way up the West Branch of the Penobscot, into what is now the Millinocket area, paddling through the interconnected lakes and marveling at Katahdin looming in the distance. It was there they met up with two Penobscot men who warned the group that the river levels between Katahdin and Chesuncook Lake were too low to traverse. On Oct. 8, they climbed the mountain, discovering a bottle of rum and a copy of Maine’s Constitution someone else had left at the summit.

Once Chesuncook was passable, they paddled up the Allagash, attempting to make it to the St. John Valley within 10 days. Treat constantly noted in his journal the quality of the soils, the types of trees growing, and the suitability of various spots in the rivers for mills and dams. By Oct. 23, they had reached Madawaska, and stayed two days with a man named Simon Hebert, a wealthy local resident of French descent.

Following the St. John River for another 50 miles, the trio crisscrossed the rather nebulous borders between Maine and New Brunswick — borders that would not be finalized for another 23 years, when the Webster-Ashburton Treaty was signed in 1843. Not far from present-day Fort Fairfield, on Oct. 26, Treat and Neptune decided to follow the Aroostook River as far as they could, but by Oct. 28, they had to turn back due to low water.

By Oct. 30, they were back in the St. John, which already had ice forming in it, and on Nov. 1, they found themselves in Houlton. From there, it was a hasty slog down the Eel River and the Mattawamkeag River, as the weather was getting colder and they were running out of food. On Nov. 16, they were back on the Penobscot River, and on Nov. 20, they arrived back in Bangor, where the journal rather abruptly ends.

A window into the past

In 2007, Micah Pawling, a history professor at the University of Maine, published a book called “Wabanaki Homeland and the New State of Maine: The 1820 Journal and Plans of Survey of Joseph Treat,” an annotated version of Treat’s journal and map.

Pawling, who has worked extensively with the Wabanaki confederation over the years, was drawn to Treat’s journal for a number of reasons — not least because it paints a picture of a part of Maine that was yet to be irrevocably changed by dams, farms and other development.

“This document gives us clues about what the river looked like before major dam construction,” Pawling said. “In that sense, it’s an incredibly important document, because it’s kind of the last time we see this part of Maine the way it was before settlers came in and changed everything.”

Among Pawling’s closest collaborators on the book was James Francis, the Penobscot Nation’s tribal historian. Francis was already familiar with Treat’s journal — in large part because the journal contains some of the first known written examples of many Wabanaki place names.

“It’s an early Penobscot voice in the historic record,” Francis said. “We value it for that reason. It’s a snapshot in time of how our ancestors used the landscape. It’s the first time you hear some of these place names. Thoreau does it, too, but that’s many years later.”

Though large swaths of Maine’s interior were uninhabited aside from Wabanaki people moving seasonally along the rivers, other parts were inhabited — by a surprisingly diverse population of indigenous and European people. French, Irish, Scottish and English people lived alongside Penobscot, Passamaquoddy and Maliseet people.

“From their point of view, Maine is all new and unexplored,” Francis said. “From the point of view of the Wabanaki, this is our backyard.”

Though the declaration that all the islands in the Penobscot River north of Old Town belonged to the Penobscot people was made in 1818, two years before Treat and Neptune’s journey, the journal is one of the few documents that show what life was like before things changed forever — and how intimately connected the Wabanaki were to the water and the land.

“It shows how sophisticated riverine people were,” Francis said. “With our current fight over jurisdiction of the river, it’s even more important to note how we were stewards of this river for all those generations. It’s not just a record of these romantic place names. It’s a record of our knowledge and expertise.”

Time is like a river

It goes without saying that the Maine of 2020 is a very different place from the Maine of 1820, in countless ways both good and bad.

The pristine rivers Treat and Neptune paddled through 200 years ago are today full of dams and development, and are polluted — though, as organizations such as the Penobscot River Restoration Project will point out, not as polluted or full of dams as they were 30 years ago.

Treats and Neptunes still live in Maine. Neptunes continue to hold important positions in Wabanaki society, as chiefs, council members, historians, artists and elders. Though Joseph Treat didn’t have any children of his own, descendants of Treat’s siblings and cousins still live along the Penobscot.

The Wabanaki people today claim ownership of just a fraction of the lands they held back then, much of which was brokered by the Maine Indian Land Claims Settlement Act of 1980. The $81 million settlement was the second-largest tribal settlement in U.S. history. The act also effectively stripped the tribes of sovereignty provisions enjoyed by other tribes, and the tribes say it denied them the ability to prosper economically and culturally. Negotiations on tribal sovereignty were reopened last year, and a task force put together 22 recommendations into a bill that, if it succeeds, would give the tribes the same rights as other federally recognized tribes on areas such as gaming, fishing, and taxation.

Though white people later Anglicized their spellings, the place names Neptune gave to Treat remain in nearly every corner of the land and water they traversed: Ambajejus (Umbojeejos), Wytopitlock (Ettopicklock), Meduxnekeag (Maduzenukeek), Mattawamkeag (Madawamkee) and Katahdin (Ktaadne).

And the most efficient way to navigate Maine’s rivers and streams is still by canoe — a technology honed and perfected by indigenous people.