Maine’s statehood is irrevocably tied to the defining issue of its time: Slavery

As soon as the United States won its independence from Britain, Mainers were advocating for the state’s secession from Massachusetts.

There were lots of reasons for Maine to be its own state — Maine and Massachusetts have never shared a border, their demographics were and remain different, and Maine’s then-booming fishing, shipbuilding, farming and lumbering industries were making the region its own economic powerhouse.

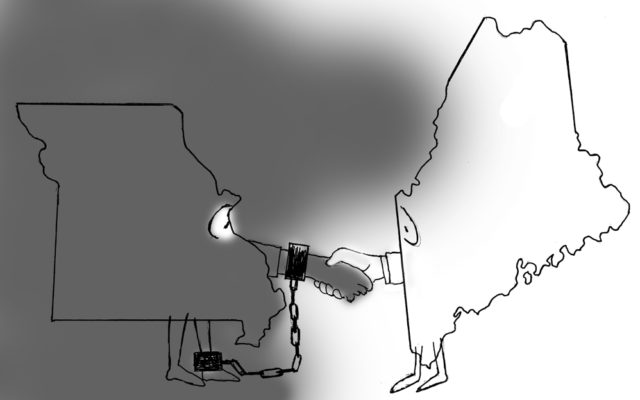

But it was an issue that continues to be central to the ongoing story of the United States — the enslavement of kidnapped African people — that is irrevocably tied to Maine’s independence, thanks to an 1820 federal agreement known as the Missouri Compromise.

The compromise was that Maine, then part of a free Massachusetts that would not allow slavery itself, would only become a state if Missouri were also allowed to become a state and be allowed to have slavery. The idea was that such an agreement would “maintain the balance” between the congressional representation of free and slave states.

The Missouri Compromise was among the first federal decisions that would lay the foundation for the issue the Civil War would be fought over more than 40 years later. It created lasting tensions between northern states, which generally viewed slavery as a barbaric and immoral institution, and southern states, which wished to maintain their rights to own human beings.

“The statehood question was debated for five decades before it actually happened, but when Congress gets caught up in the issue, it becomes as much about this fundamental issue in American politics as it does about our statehood,” said Liam Riordan, a professor of history at the University of Maine.

The road to statehood began as early as the 1780s, just a few years after the Treaty of Paris affirmed the country’s independence from England. Maine’s first newspaper, the Falmouth Gazette, was founded in 1785 for the main purpose of promoting statehood. It issued a call to action for a meeting on discussing statehood in one of its first editions Sept. 17, 1785.

[image id=”2936309″ size=”full” pos=”center” /]

It took 35 more years for it to happen. That was due to disagreements between newly settled residents of the interior parts of the state, who tended to favor independence, and more conservative, older residents of coastal communities, who tended to not want to secede, Riordan said.

Most of those coastal residents were also Congregationalists, descendents of the Puritans who first settled in New England. As Congregationalism was the de facto state religion of Massachusetts, every municipality was required to have a Congregationalist minister, paid by the state. If Maine became its own state, it meant that Congregationalism could be usurped by other denominations, including Methodists and Baptists, which then dominated the interior.

Maine residents — the property-owning white men among them — voted on the statehood issue six times between 1792 and 1819. The 1807 vote failed by a wide margin. Voters also rejected statehood in two more votes in 1816, as the War of 1812 had just ended, and borders and fishery rights were still being deliberated between the U.S. and England that wouldn’t be fully settled until 1842.

By 1819, the war was over, Maine was again prospering and opinions had changed. The July 26, 1819, vote was overwhelmingly in favor of statehood, though something that shouldn’t have taken more than a month or two to enact ended up taking nearly eight months.

Missouri had petitioned to become a state earlier in 1819, but its request was not granted at the federal level, with Southerners chafing at federal restrictions on slavery and Northerners not wishing to allow more slave states into the Union. When Maine submitted its petition for statehood, however, Southerners jumped at the chance to make a compromise — Maine would be free, Missouri would not and the Senate would remain balanced.

“Maine essentially gets tossed into this mess at the national level,” Riordan said. “The issue of slavery was not really front and center in [Maine’s] statehood debate, but then suddenly, it was.”

It took eight months of protracted negotiations for that “compromise” to be reached, with much of the debate stemming from abolitionist Maine congressmen, who fervently opposed the spread of slavery anywhere — so much so that they were willing to torpedo the entire Maine statehood movement, just to keep slavery from spreading.

Nevertheless, the legislation was made final in March 1820, and on March 15, Maine officially became a state. Though the compromise initially helped soothe some tensions, it also enshrined the very things that would later tear the nation apart. In 1854, the compromise was effectively repealed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act. In 1861, the Civil War began.

“It shows how slavery and blackness are truly fundamental to our understanding of our country,” Riordan said. “Maine may be one of the whitest states, but the reason we are a state is undeniably tied to how this country has dealt with those issues. It shows how connected we are to national issues.”