Basic dude stuff is needed now more than ever

The first thing I notice about Patrick McNamara’s video on the LinkedIn business networking site? It is low-tech. Positioning his smart phone vertically, Mr. McNamara looks directly into his phone’s camera. Sometimes we see his full face. Sometimes we see his head profiled. And sometimes part of McNamara’s face is out of our field of view. Each video is just under a minute in length, with McNamara offering on each five-to-six lessons on what he calls “basic dude stuff.”

It’s brilliant. A quick review of basic life lessons, skills, and manners lacking quite often in today’s world.

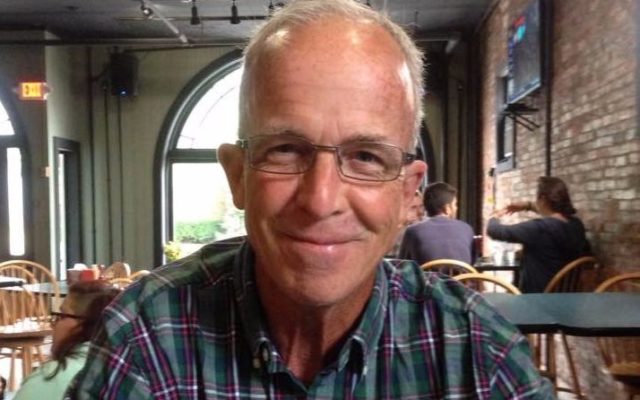

Pat Mac, as McNamara refers to himself, is an impressive looking guy. I wouldn’t want to be on his bad side. After 22 years in US Army special operations, Mac is now President of his TMAC, Inc. which offers training in self-offense/defense and tactical shooting.

At first glance, some of Mac’s “basic dude stuff” seems natural coming from a US Army special ops guy:

- How to clean a gun

- How to replace a Zippo lighter flint

- Knowing the parts of an internal combustion engine

- How to tie knots

- Knowing the mossy side of a pine tree faces north, or

- How to sharpen a knife blade using a whetstone

But Mac offers unexpected “basic dude stuff” as well. Viewers see a few seconds of Mac:

- Giving his wife a foot rub

- Cooking the family breakfast

- Mopping the kitchen floor

- Attending his wife’s work’s Christmas party

- Removing his hat in a restaurant

And my favorite, Pat Mac talking on his cell phone saying, “Take care, Mom. Thanks for being my mother. I love you too. Bye.”

His “basic dude stuff,” says Pat Mac, “knows no gender.”

I appreciate anyone, but especially people with experience, passing along life basics or skills to younger generations. Patrick McNamara is the latest to come to my attention, and his video format is unique and effective. They are short and to the point.

In 2016 I discovered, “Book of Man — A Navy SEAL’s Guide to the Lost Art of Manhood.” Author Derrick Van Orden writes in his book’s introduction: “The idea to write this book occurred to me years ago when I began to notice that American men no longer appear to understand some of the most basic skills that used to be associated with manhood.”

Mr. Van Orden’s book includes lessons on many skills including fishing, cooking, shoe polishing, fighting, and necktie tying.

And in 1989, long before I was aware of either Pat Mac or Derrick Van Orden, the great American writer, John Dos Passos, impressed me along similar lines in his 1958 essay, “A Question of Elbow Room.” In his essay, Mr. Dos Passos laments and warns against cultural norms lost to America in moving into technology and types of work, that would, if we were not careful, dehumanize us.

“The thing the Americans — townsmen, fishermen, and sailors of the New England seaports; planters and merchants from the Chesapeake; hunters and fur traders from the Ohio — had in common was that they thoroughly understood the world they lived in. The technology was simple.”

Americans knew how to read, write, build houses and barns, fix gasoline and steam engines, sew, knit, carve; they knew how to plant and grow gardens, how to chop trees and use the wood to build and to warm themselves.

“Any tolerably bright individual knew from personal experience how wheeled carriages and sailing ships worked, understood the processes of agriculture and manufacturing, the use of money and the technique of buying and selling on the market place. Much more important, they all knew by direct personal experience how the different kinds of people worked who made up their society,” wrote Dos Passos.

Patrick McNamara, with his “basic dude skills,” and others like him, are helping to keep society tolerably bright. It’s important work, perhaps now more than ever.

Scott K. Fish has served as a communications staffer for Maine Senate and House Republican caucuses, and was communications director for Senate President Kevin Raye. He founded and edited AsMaineGoes.com and served as director of communications/public relations for Maine’s Department of Corrections until 2015. He is now using his communications skills to serve clients in the private sector.