Maine’s wage gap is a burden on women — not a choice

By Anne Gass and Sue Mackey Andrews

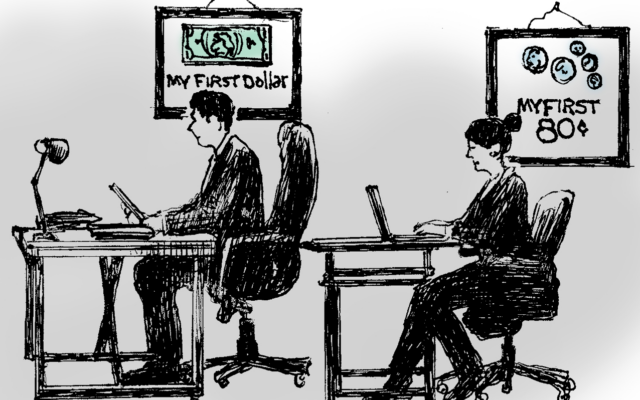

The gender wage gap is alive and well — and it is not something that Maine women are “choosing.â€

There are a wide variety of social, economic, structural and systemic drivers of the gender wage gap. In 2023, men across the country earned more than women regardless of the industry or type of work. Even in industries dominated by women, such as nursing or teaching, men earned more.

To suggest that these disparities exist because women have chosen them, as was said in a recent column published by the Bangor Daily News, is both dangerous and untrue. Wage discrimination still exists — and it can be found across a variety of professions. In 2022, for example, Maine clinical psychologist Clare Mundell won a discrimination case in which she was being paid half as much as her male colleagues.

Women also report higher rates of sexual harassment in the workplace than men do, and Black women in particular experience a disproportionate rate of sexual harassment at work. Harassment can prompt a job change for safety reasons, even if it means going into a lower-paying role. Sexual harassment is especially prevalent in male-dominated professions, which can limit women’s access to the higher-paying jobs in these industries.

In addition to the impacts of wage discrimination and harassment, the United States has lagged behind other nations on paid leave, child care and other family-friendly policies that allow parents to participate fully in the workforce. Women are often forced to make decisions about the tradeoff between a career and a family life, and these issues have only grown more pronounced since the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Maine Permanent Commission on the Status of Women’s 2022 Report illustrated the impact of COVID on Maine women. More women than men have care responsibilities outside of their full-time jobs — for their children, partners or older family members. On average, those care responsibilities amount to 30 hours every week: almost the equivalent of a full-time job.

The commission’s research also highlighted the need for high-quality and affordable child care as one key part of promoting economic opportunity for Maine women. Recent investments in child care and paid family leave are something to celebrate in Maine — policies like these help close the wage gap. But there is more to be done. Among Maine parents, the median income of mothers was 68.1 percent of the median income of fathers in 2021, and national data show that men tend to earn more after becoming parents, whereas women earn less. These disparities have impacts across the lifespan.

According to a report from the University of Southern Maine, older Maine women are more likely than men to be living in poverty, more likely to live alone, more likely to rent their homes and more likely to need long-term services and supports but be unable to afford them. After decades of working lower-paying jobs that make it challenging to save for retirement or doing part-time work so they can wear the many hats of parenting and caregiving, older Maine women shoulder a heavy burden. This is one of the most heart-wrenching outcomes of the wage gap — and it is preventable.

This disparity and its impacts are not evenly distributed. Nationally, for every dollar earned by a white, non-Hispanic man, Native American and Alaskan Native women earned 54.7 cents, Hispanic or Latina women earned 57.5 cents, Black women earned 69.1 cents, and white, non-Hispanic women earned 80 cents. A national survey of LGBTQ+ individuals found that transgender women make 60 cents for every dollar earned by a typical U.S. worker.

Here in Maine, the median income in 2022 for men who worked full time, year-round was $9,370 higher than it was for women who worked full-time, year-round. Gov. Janet Mills proclaimed March 12, 2024, National Equal Pay Day in Maine to recognize how far into 2024 women have to get before they make the same amount that men made in the 12 months of 2023.

In an era when women’s agency and decision-making power is threatened, now is the time for us to advance policy that promotes economic opportunity for everyone, rather than to ignore systemic challenges that leave women with limited choices — or no choice at all.

Gass and Mackey Andrews are members of the Maine Permanent Commission on the Status of Women, a government appointed group dedicated to improving opportunities for Maine women and girls. Gass lives in Cumberland County, is a small-business owner and independent historian. Mackey Andrews lives in Piscataquis County and works in the field of public health.Â