Maine needs to address reasons for declining life expectancy

“According to a new study in [the Journal of the American Medical Association] JAMA, life expectancy at birth stopped increasing since 2010 and actually decreased in the US for three consecutive years. To put this in perspective, the last time we saw three consecutive years of declining [life expectancy] was 100 years ago, coinciding with the flu epidemic of 1918.”

That is the lead paragraph from a December 29, 2019 email update I received from Dr. Peter Attia with the equally attention grabbing subject line: “Why is life expectancy in the US declining?”

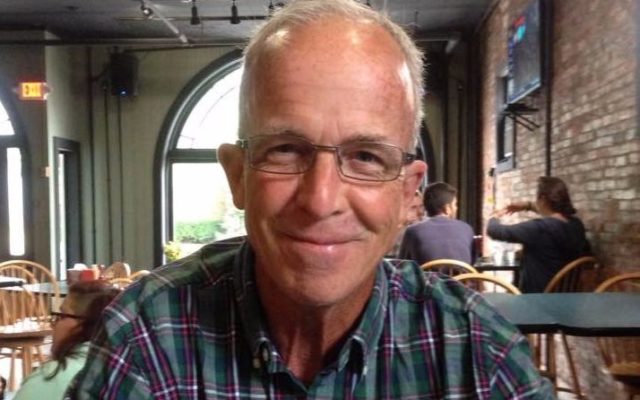

Peter Attia is an interesting man. I’ve listened to Attia a few times as a podcast guest. I subscribe to Attia’s own podcast, “The Peter Attia Drive.” It is entertaining, educational, and sometimes tough sledding. When Attia and/or his guest lock in to medical jargon, I am listening to a conversation in foreign language.

The “About” section of Attia’s blog describes him, in part, this way: “Peter is the founder of Attia Medical, PC, a medical practice.., focusing on the applied science of longevity. The practice [is concerned with identifying ways] to increase lifespan.., while…improving…quality of life.”

Attia, in my experience, is open to non-traditional medicine practices and ideas for increasing lifespan and healthspan. That openness is one Attia characteristic I like best. Plus he strikes me as a realist optimist.

So I was struck in Attia’s email when he wrote of the JAMA study, “Perhaps surprisingly, increased mortality rates in midlife — defined rather broadly as 25-64 years old — are driving the stall, and eventual decline, in LE. Within this group, the largest increases in mortality rate occurred in the subset of people aged 25-34, and it was the increase in drug overdoses, suicides, and alcohol-related diseases that were identified as three key causes of death in this group.”

The largest increase in deaths is among 25-34 year olds due to drug overdoses, suicides, and alcohol-related disease? What are we doing to ourselves? That’s the prime of life.

Citing the JAMA research, Attia said in his email, “Between 1999 and 2017, midlife mortality from drug overdoses increased by nearly 400%.., alcoholic liver disease increased by 40.6%.., and suicide rates increased by 38.3%. This triad is referred to as ‘deaths of despair’….”

Digging a little deeper into the JAMA research I discovered the two areas in the US with “the largest increases in midlife mortality rates” are the Ohio Valley and New England. The three New England states and their increases in midlife mortality rates are New Hampshire, 23.3%; Maine, 20.7%; Vermont, 19.9%.

Let that sink in. Maine is among the top places in the nation where 25-34 year olds are dying from drug overdoses, suicides, and alcohol-related diseases.

Yesterday in a Tweet, US Sen. Susan Collins said, “Since 2016, Congress has boosted funding to address the opioid epidemic by 1,300 percent. To ensure those struggling with addiction are able to access the treatment they need, we must increase the number of providers to keep pace with the billions of dollars in new resources.”

Maybe putting more tax dollars into opioid addiction is an answer. For the moment I’ll assume it is.

But based on my personal and professional experience with addictive substances there is a major component to tackle. The component manifests itself in areas such as politicizing environmental issues. Stop hammering despair into our school children. School kids should be curious and enthusiastic about finding solutions, new discoveries, new interests, and new ideas in all areas of their lives.

But if we continue teaching school children and others to despair — there’s not enough money in the world to arrest that downward spiral.

Scott K. Fish has served as a communications staffer for Maine Senate and House Republican caucuses, and was communications director for Senate President Kevin Raye. He founded and edited AsMaineGoes.com and served as director of communications/public relations for Maine’s Department of Corrections. He now works in the private sector.