How this Dover-Foxcroft man came to possess a 138-year-old murder weapon

Growing up in Dover-Foxcroft, Carlson Williams’ family often told stories about local history around the dinner table. One of his favorite tales to hear was also among the most gruesome: the story of the murder of Alvin Watson in the nearby town of Parkman in June 1881.

“We’d tell the story around the Thanksgiving table,” said Williams, 80, a retired engineer who returned to his hometown two years ago with his wife, Carolyn, after living in Connecticut for decades. “It does sound like kind of a dark thing to talk about at Thanksgiving, but it’s really quite a story.”

Williams comes from a long line of lawyers and judges in Piscataquis County, which is how he’s come to possess the key piece of evidence in the case against Watson’s alleged killer: the hand-forged, four-inch dagger used to kill Watson.

Contributed image

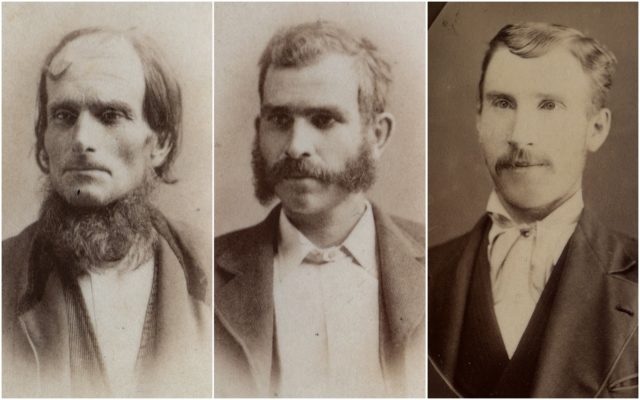

19TH CENTURY MURDER — From left, Benjamin Chadbourne, Wallace Chadbourne and Alvin Watson. The Chadbournes were convicted of murdering Watson in 1881 in Parkman.

A Maine history enthusiast, Williams has tracked down all the information he can find on the Watson murder, and has compiled what he believes is an accurate telling of the story, which he has given talks on at local libraries since moving back to Maine.

The story starts in the 1870s on the Chadbourne farm in Parkman. Benjamin Chadbourne was, according to local lore, a famously hot-tempered man who at that time was married to his third wife, Caroline. He had two sons from previous marriages: Wallace with his first wife, and Byron with his second.

In 1877, at age 29, Wallace Chadbourne married his stepsister, 16-year-old Eva. The couple had been farming the land alongside his father when a new neighbor moved onto the farm next door: Alvin Watson, an unmarried man newly arrived in Parkman. The situation began to unravel when Wallace and Eva temporarily separated in 1879. Wallace left town and found work in Dexter, and Eva stayed on the farm.

According to Williams, when Wallace Chadbourne returned to Parkman in 1880, he began to suspect that Eva had been unfaithful to him with Watson. When Eva gave birth to a child in 1881, he suspected that Watson might be the father. Watson, in turn, began to harass Wallace Chadbourne. Threats and physical violence became common.

“There were constant back-and-forths, and Watson really egged Wallace Chadbourne on,” said Williams. “They were at each other’s throats, and eventually, the Chadbournes decided to really do something about it.”

On the night of June 26, 1881, Alvin Watson was brutally murdered. He was found the next morning with multiple stab wounds in his chest and back, and with his throat slit. A local doctor who examined the body found 49 stab wounds.

Suspicion immediately turned to the Chadbourne family. Wallace and his father denied any wrongdoing, and directed the blame at a different suspect: the younger Chadbourne son, Byron.

Byron Chadbourne was born deaf, and had received almost no education. He was, according to Williams, belittled and abused by his family. As such, it was extremely difficult for most people to communicate with him. Byron, then just 18 years old, was arrested and charged with the murder of Alvin Watson, and thrown in jail to await trial.

Alvin Watson’s father knew something didn’t add up, between the way the murder went down, and the fact that both Benjamin and Wallace Chadbourne were adamant about placing the blame on Byron. A special investigator from Bangor was called in, and Watson’s body was exhumed for a full autopsy. Benjamin and Wallace claimed Byron had stabbed Watson with a folding jack-knife, but the autopsy showed that the stab wounds were much deeper than what such a knife could produce.

Furthermore, Byron Chadbourne was a slight 120 pounds, while Watson was a large and muscular man who could easily have fought off the young man. The bloody footprints found at the scene of the crime were from a much larger person than Byron. And Watson had actually grown friendly with Byron, inviting him over for meals and letting him stay at his house so the 18-year-old could avoid his abusive family.

Officials searched Benjamin Chadbourne’s house and found a knife with a blade that matched the wounds on Watson’s body, and in mid-July, charges against Byron were dropped, and murder charges were brought against father and son.

Attorney Joseph Peaks successfully prosecuted the case and won, and both Benjamin and Wallace Chadbourne were found guilty. Benjamin spent the rest of his life in prison, and Wallace spent 22 years in prison before being released in 1904 at the age of 55.

Byron Chadbourne, upon whom many in the community had now taken pity, was sent to the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut.

“It actually ended up being a much happier ending for Byron than it otherwise could have been. He was taken out of this awful situation, and brought to a place where he could have an education and be treated like a human being,” said Williams.

The criminal justice system in Maine in the 1880s did not have the same sort of regulations as it does today to ensure that evidence was properly stored, so after the trial, prosecutor Peaks took home the murder weapon, storing it in a cigar box alongside photographs of Benjamin and Wallace Chadbourne and Alvin Watson. That cigar box was passed down to his son, Francis Peaks (one of the namesakes for Peaks-Kenny State Park in Dover-Foxcroft), who served in the Maine House of Representatives and was a lawyer in Piscataquis County.

When Francis Peaks died in 1974, his secretary, who was the executor of Peaks’ estate, gave the box and its contents to a local judge, Matthew Williams — Carlson Williams’ father, who himself died in the 1990s and left the box to his son.

“It’s been in our family all this time,” said Williams. “It’s got to be fairly unusual, to have something like that that you can trace all that history back to.”