Communicating comes down to the heart

Here’s a contrast in the speed of communications: I am reading “James Marshall: Definer of a Nation,” by Jean Edward Smith. Marshall was, among other things, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, largely responsible for shaping that court and, to a great extent, our nation.

Prior to serving on the Supreme Court, Marshall served as a U.S. ambassador to France in 1797-98 — which is where I am in the Marshall biography. Today a U.S. ambassador to France would simply communicate with the U.S. government by secure phone lines or by secure email and video conference. My point is, the communications are immediate.

In 1797, the only way to communicate was by handwritten letters carried by sailing ships to the United States from France. The voyage length was, at best, one-and-a-half months. At worst, the ship was lost at sea courtesy of storms or attacks by other ships. The letter is never delivered. It is weeks, maybe months, before the letter writer in France finds out. Or they may never find out.

The slow communications workaround in the late 18th century was for the U.S. government to trust Marshall and the two other ambassadors with him to negotiate and reach agreements with the French government that best serve the United States. What happened if our ambassadors wanted input on a negotiation point from the U.S. government? Unless the French officials and the U.S. ambassadors were willing to pause negotiations for six months — time enough for the negotiation point to sail to the U.S., be delivered to Washington, DC, read and considered, and a written response sent by ship back — the ambassadors simply used their best judgment.

In contrast to that snail’s pace, last night I did a double-take at a TV commercial about a kitchen sink faucet with voice activation and motor sensor technologies. From the faucet’s website:

“Just say the words to turn the water on, fill containers to a preset level or dispense a specific quantity. In addition to voice control, this touchless faucet includes a motion sensor that turns water on and off with a wave of your hand.”

Then this morning on talk radio, a Congressman described to show host Hugh Hewitt what it’s like in the President’s situation room during discussions about Iranian drone missile strikes on Saudi oil facilities. In addition to the people in the room, digital technology allows experts to be piped in, from virtually anywhere in the world, to the meeting on two-way video screens.

You and I, meanwhile, go through our day on computers, smartphones and tablets. Social media provides us the means to communicate globally. In the last two weeks I’ve had email sent from fans of my drumming blog living in Italy and Brazil. My initial reaction is always, “How cool is that?”

We digitally stream TV, music, radio, at home, in our cars, at work. Always at our fingertips. And as Alexa — and now kitchen faucets are proving — we are less and less needing to bother with fingertips.

Still, whether we’re writing letters, Tweeting, or asking Alexa for tomorrow’s weather, human nature remains the same. That we have the technology to send rapid fire messages to each other is no guarantee our messages will be honest, kind, helpful, or sincere.

According to the biography I’m reading, in 1797 John Marshall was as frustrated with the political spin and skullduggery of his French counterparts as I think a majority of today’s Americans are with the torrent of lies, spin, deceit, selfishness, and fraud saturating much of social media; particularly news outlets and political campaigning.

Using communications to do damage, or using the same communications to heal, to make life better, to tell the truth. The choice has always been, and will always be, up to individuals. It comes down to the heart.

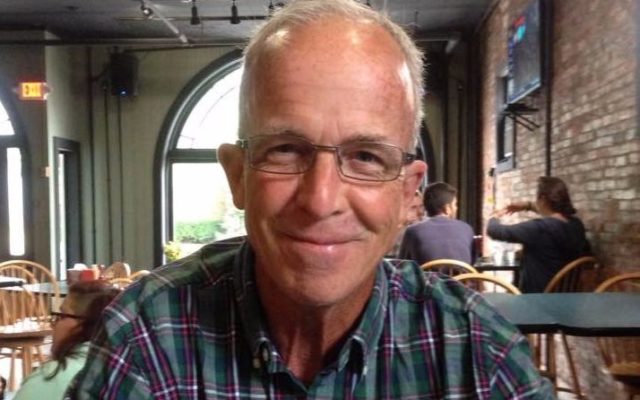

Scott K. Fish has served as a communications staffer for Maine Senate and House Republican caucuses, and was communications director for Senate President Kevin Raye. He founded and edited AsMaineGoes.com and served as director of communications/public relations for Maine’s Department of Corrections until 2015. He is now using his communications skills to serve clients in the private sector.