What Maine is doing to prevent and treat head injuries in youth athletes

Concussions continue to be the most discussed health care topic these days related to youth athletes in such high-profile and high-contact sports as football and soccer.

Jackie Tourtelotte has been on the front line of injury prevention in high school sports in eastern Maine for more than a decade. She started at Orono High School and for the last eight years has been the certified athletic trainer at Foxcroft Academy in Dover-Foxcroft.

And while no strategy in pursuit of a 100 percent healthy outcome is perfect, she appreciates how increased awareness about concussions and other major health issues has changed the mindset of those playing the games.

“One of the big things now is that I have kids come to me and report that, ‘My teammate isn’t acting right, and they got hit and I’m worried about them.’ That’s really hard for a teenager to do — to step up and say something like that about a teammate,” she said.

“And sometimes kids will come to me about themselves. More people are being proactive about themselves and their teammates, and that’s awesome.”

Much of that increased awareness is rooted in national and local educational efforts and the implementation of tools that promote injury diagnosis and prevention.

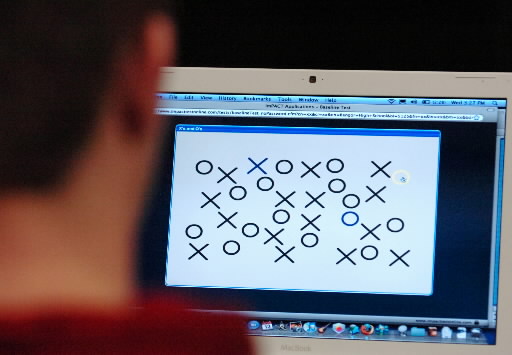

One tool being used in more than 100 Maine high schools today is ImPACT testing: Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing. It involves taking a 40-minute computer test known that establishes a baseline of their neurological function. The program measures verbal and visual memory, processing speed and reaction time.

Student-athletes are tested prior to each new academic year for potential comparison with subsequent tests in the event they are suspected of suffering a head injury during an activity. Those tests then are incorporated into the student’s treatment plan.

The Maine Concussion Management Initiative, based at Colby College in Waterville, provides schools access to ImPACT testing as well as myriad educational initiatives related to the care of head injuries.

“I think over the last 10 years the MCMI has done a fantastic job reaching out to schools in providing opportunities whether it’s the ImPACT testing or just educational materials,” Mike Burnham, assistant executive director at the Maine Principals’ Association, said. “I think statewide we’ve seen a greater awareness from coaches to parents to the athletes themselves, and I’d like to think we’ve seen an impact on the athletes and when they return to the academic setting and athletic competition.”

According to the initiative, 10,000 to 12,000 Maine student-athletes undergo baseline ImPACT testing annually, a number that has been relatively consistent in recent years.

ImPACT testing also is gradually making its way to the younger grades, with approximately 20 middle schools statewide implementing the program during the 2017-2018 year through MCMI.

“We are seeing some penetration into the middle schools, but there are some challenges with ImPACT,” MCMI director Dr. Paul Berkner said. “It has not upgraded its platform to a tablet (computer), so schools that use only tablets are having some struggles with it, but we’ve been pretty consistent over the last four or five years in terms of the number of schools and the number of tests we’ve done.”

MCMI soon hopes to cover even younger athletes through a new initiative called the Youth Concussion Project. The fragmentation of the youth sports community may make that a challenge, although a pilot presentation of that program in 17 Washington County schools 18 months ago reached approximately 1,000 pupils.

Another goal for MCMI is to increase use of its already existing Head Injury Tracker, a tool for certified athletic trainers and school officials to report and track concussions.

“We’ve had moderate acceptance of using that tool for the last three or four years,” Berkner said. “Schools are stretched thin, and this is something added that they would have to do, and the state does not mandate reporting of concussions through the Department of Education or Department of Health and Human Services, so there’s no real carrot for them to do it.”

But there is an incentive.

“If we could get 115 Maine high schools to use that tool then we could be tracking (by extrapolation) how many concussions were happening within the schools across the state,” he added.

Work done by the MCMI is part of a multifaceted awareness effort that also includes the introduction of more safety-minded equipment. One is a football tackling wheel designed to help players learn proper tackling techniques, and ongoing research and educational initiatives such as the Heads Up program developed by USA Football.

The MPA has been active in developing and updating policies or guidelines related to preseason practice acclimatization and the number of quarters any football player should play.

“The truth of the matter is most of the coaches are already doing those things,” Burnham said. “Coaches don’t want their kids to be hurt in practice because then they’re not available for games.”

All involved believe communication remains a key to both injury prevention and dealing with head injuries in a timely and efficient fashion.

“No one wants to sit out of sports,” Tourtelotte said. “I got a couple of concussions in high school and I didn’t want to sit out of sports, but then there was no one to go to and no science on it. It was just, ‘Go back to play when you feel better.’

“Today I’d rather talk to a hundred kids that don’t need my help just to be sure I didn’t miss that one kid who needed help and didn’t get the proper care.”