Preserving family memories teaches us about ourselves

My grand uncle Charlie Fish was one of my paternal grandfather’s two brothers. What little I know of Grand Uncle Charlie is mostly from my father. Uncle Charlie could play any musical instrument, and he was his family’s black sheep, my father said.

That is all I know of a relative I would have liked to have known. I started thinking of relatives who were part of my life. What firsthand details of them will my future family members have?

I should put the memories I have in writing.

My Uncle Bob Fish is the first relative I am writing about. My lifelong love of drums and music stems from Uncle Bob. Bob was my father’s youngest brother. Uncle Ivan Fish was the middle brother.

All last week I carried a pocket size spiral notebook and a pen for jotting down my memories of Uncle Bob. It was surprising how few first-hand memories I have. In my “Spread the word about suicide prevention” column (May 28, 2017 Piscataquis Observer) I wrote about Uncle Bob.

With this latest written profile I was braced for a long process of remembering and writing. I mean, how could it be otherwise?

But it is otherwise.

Restricting my first draft memories to one-on-one accounts with Uncle Bob, I am surprised there are so few. But Uncle Bob died when I was 14 years old. He lived in Auburn, MA, I lived in Huntington Station, NY, with 200 driving miles between us. Once or twice yearly, usually Christmas, sometimes Thanksgiving, my parents packed their five kids into the family car for Auburn, MA.

We celebrated Christmas at home, a second time at my maternal grandparents’ home, a third time at my paternal grandparents’ home. I would only see Uncle Bob, when he was around, at my paternal grandparents’ home, which doubled as Charles R. Fish Tree Nursery, my grandparents’ family business.

My pocket notebook now has maybe a dozen personal recollections of Uncle Bob. When finished note making I feel certain I will have more memories. Certainly, if I write about recollections of Bob in absentia — listening to his Gene Krupa “China Boy” record; sitting at his drumset alone in the Quonset hut shaped nursery supply shed — I will have more stories.

My Uncle Bob memories pass like old movie clips in which we were both actors.

There is the time Uncle Bob, my brother, Craig, and I were together in the nursery drafting room. A large room above the nursery office building attached to my grandparents’ home, the drafting room was where my grandfather, and Uncle Ivan, created mechanical drawings of landscaping projects. It was also the room where Craig and I would draw, read comics, and listen to late ‘50s/early ‘60s rock tunes on radio.

Uncle Bob is showing me two ways to hold drumsticks: traditional grip and match grip. Learn to play using both grips, learn the drum rudiments, and “then just play,” Bob advised.

Uncle Bob’s drum lesson holds true to this day.

My last memory of Uncle Bob is from a dream. Years after his death, I dreamed I was in a house, walking room to room. Entering a new room, I came face to face with Uncle Bob. Seated on a couch, he wore a white t-shirt and dungarees. Bob appeared to have just awakened, or to be getting over an illness, feeling just well enough to be dressed and out of bed.

Standing in the entryway between rooms, I said, “Uncle Bob! I didn’t know if I’d ever see you again. How are you?”

In a tired, reassuring voice, Bob answered slowly, “I’m okay. I’m okay.”

Gathering my Uncle Bob memories for others, I find I am learning anew, Uncle Bob lessons for myself.

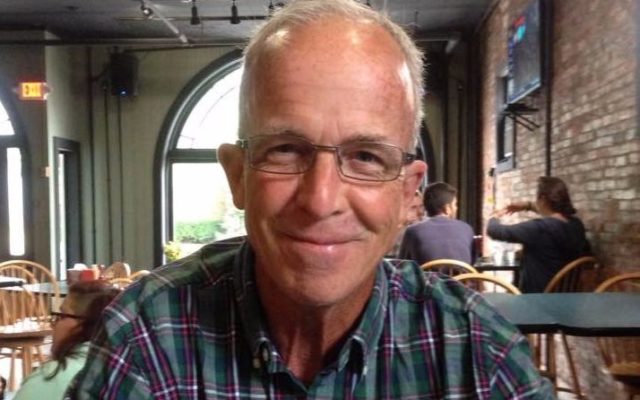

Scott K. Fish has served as a communications staffer for Maine Senate and House Republican caucuses, and was communications director for Senate President Kevin Raye. He founded and edited AsMaineGoes.com and served as director of communications/public relations for Maine’s Department of Corrections until 2015. He is now using his communications skills to serve clients in the private sector.